Great Photographers: Edward Curtis

I discovered Edward Curtis by accident while researching the Pictorialist movement at the end of the 19th century. It didn’t take me long to fall in love with his photography.

Curtis undertook and eventually completed "the greatest photographic odyssey in American history, arguably world history." (Timothy Egan, Biographer)

His images excite me more than any others I have ever seen.

There's a majestic sorrow to them. Implicit in every single image, is the bleak future. A future that is bereft of magic. A future of conformity and complicit submission to 'progress'.

It's the end of Wilderness. The end of the untamed. The end of gods in the grasslands and spirits in the mountains.

The end of the world without owners, fences, permits, indemnity forms, safety barriers, training wheels, helmets, and signposts. A bureaucrats utopia.

And so Curtis speaks to me and I imagine what I could never have imagined without him.

That is the power of Edward Curtis.

Curtis died in 1952. His obituary, published in the New York Times, was just 77 words long. His great work wasn't even mentioned.

In the 1970s thousands of prints, negatives and plates were rediscovered in the basement of a Boston book dealer and in 2012, a single copy sold for $2.9m

Edward Curtis - Three Chiefs - Great Plains

Edward Curtis - Navaho War Gods

Edward Curtis - Red Hawk

Early Career

Curtis mortgaged his homestead for $150 and started up as a portrait photographer in Seattle, Oregon.

Despite being named after a Native American, it was illegal for Native Americans to live within the city limits. All except one. Angeline, the daughter of Chief Seattle.

At this time princess Angeline was an old woman but Curtis persuaded her to have her portrait taken. The portrait was a success. People had never seen an Indian portrayed this way before.

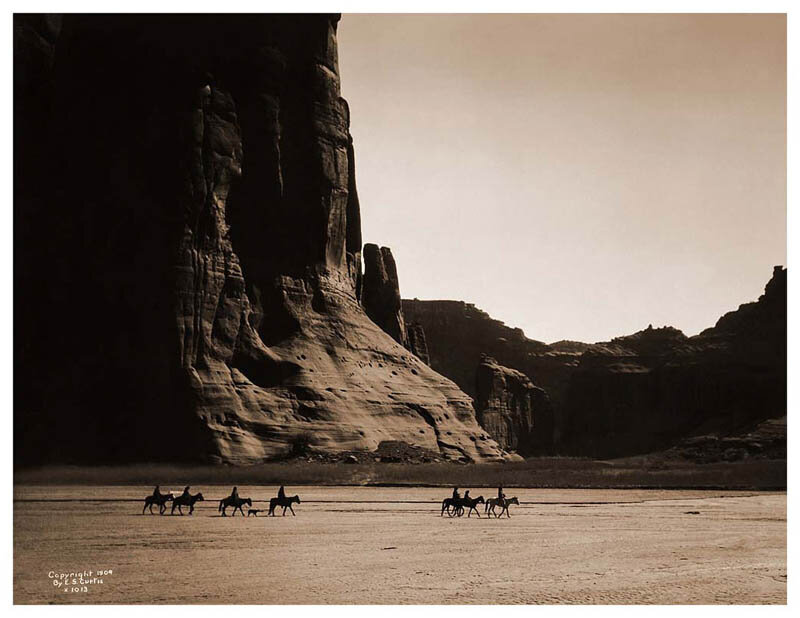

Edward Curtis 1904 - Navaho, Canyon de Chelly (this image was so cinematic in scale that it influenced early Western films) The theme is similar to earlier paintings by Albert Bierstadt,

Albert Bierstadt - View of Chimney Rock and Sioux Village

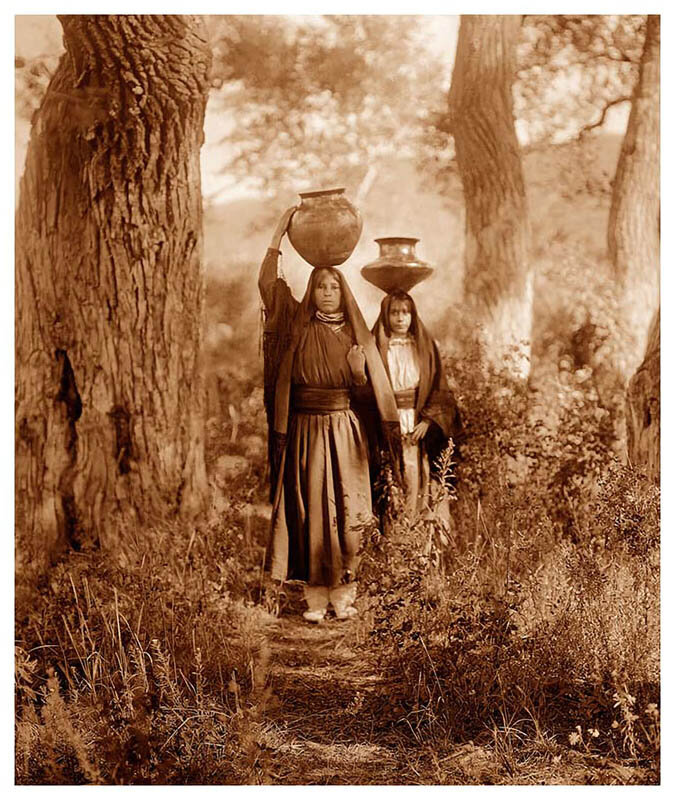

Edward Curtis 1905 - Taos water girls

In the early 20th century, a census discovered just 235,000 Native Americans on the continent. The wars were over, but the people were disappearing.

In 1900, Curtis travelled with Bird Grinnel, the founder of the National Audobon Society to witness the Sundance on the high plains of Montana. Throughout that summer, Curtis got to know the people of the Blackfeet Nation and it was there that he first had the idea to photograph these fading peoples of the plains.

Edward Curtis - “Hami'“ Dangerous Thing

I want to make them live forever

Curtis' idea, to photograph all the remaining intact Native American tribes, consumed the rest of his life.

He said to Grinnel, "I want to make them live forever."

in 1903, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce, was invited to watch a football game in Seattle. Curtis took two images and these became some of his most famous photographs.

Within a year Chief Joseph had died. Ostensibly of a broken heart.

Edward Curtis 1903 - Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce

Before long, Curtis started to understand how the culture of the native peoples of North America was being erased and replaced with stereotypes. Curtis became less detached. Seeing his photography now as advocacy.

He travelled to some of the most remote areas possible in search of untouched cultures to photograph. This was partially the result of the marginalisation of these groups, not just in society but physical marginalisation to the edges. To the wastelands no one wanted.

He visited the Makah on the far northern shores of the Pacific Coast and the Akuma in the mesas of New Mexico. Curtis was moving at a frantic pace, convinced that time was running out. The world of the Native American was fading.

Edward Curtis - Bears Belly

He wanted to record as much of it as possible before it was too late and in that effort, he became more than a photographer. Documenting rituals, language, artefacts, cultural heritage and biographies in his notebooks and in thousands of glass & copper plates and wax cylinder sound recordings.

In many cases, he did arrive too late.

“The passing of every old man or woman means the passing of some tradition, some knowledge of sacred rites possessed by no other...Consequently, the information that is to be gathered, for the benefit of future generations, respecting the mode of life of one of the great races of mankind, must be collected at once or the opportunity will be lost for all time.”

(Edward Curtis)

J.P. Morgan

In 1906, Curtis went to see J.P. Morgan, then the richest man in the US. Morgan made much of his fortune from railroads punched into the interior of the North American continent. Ironically, these were also one of the principal mechanisms in the decline of Native American cultures.

Morgan, also an art collector, agreed to sponsor the project to the tune of $75,000. This was to pay for the fieldwork and not for any developing, writing or editing. Curtis did not receive a salary.

In return, Morgan was awarded 25 volumes and 500 original prints as consideration.

With Morgan's money, Curtis was able to hire accomplices. William Myers, a journalist, Bill Phillips for general assistance and Frederick Hodge as expedition anthropologist.

Edward Curtis 1904 - Mosa, Mohave

Money problems

Throughout his travels, Curtis struggled with money. Even with Morgan's backing, the funding was inadequate. In 1916 he had a bitter divorce and had to pay alimony thereafter.

In 1919, Curtis ran out of cash. He moved to California and started work as an assistant cameraman on motion pictures and in a commercial portrait studio. It was there that he was forced by circumstance to sell the rights to a feature-length motion picture he'd produced, one of the first-ever to document Native American life, named 'In the Land of the Headhunters'.

In 1927, after returning from Alaska where he'd been working on documenting Inuit people, Curtis was arrested for failure to pay alimony.

He was desperate and sold the rights to his life's work to J.P. Morgan junior.

The final volume of Curtis' work was published in 1930.

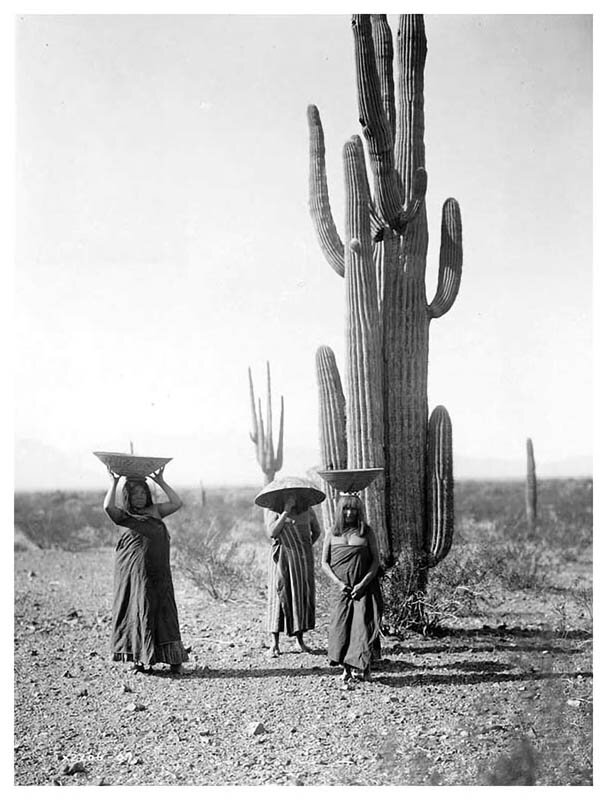

Edward Curtis - Southwestern USA

The North American Indian

Eventually, two-hundred and twenty-two sets were completed. These were published in separate volumes and collectively incorporated in a work known as the 'North American Indian'

In the course of these travels, visiting more than 80 separate groups, Curtis had taken over 40,000 glass negatives and 10,000 wax cylinder recordings. Many of these became instrumental in preserving Native American language.

In 1935, the Morgan estate sold the rights to the North American Indian to a Boston bookseller for $1,000.

The works included 19 bound sets, thousands of prints, printing plates, unbound pages and the original glass plate negatives. These remained untouched in that Boston basement until they were rediscovered in 1972.

“We say that the faces of coming generations are looking up from the Earth. So when you put your foot down, you put your foot down very carefully - because there are generations coming one after another. If you think in these terms, then you’ll walk a lot more carefully, be more respectful of this Earth.”

(Oren Lyons of the Onondaga Indians, 1930)

The North American Indian - Full Set

Edward Curtis Legacy

A new edition of Curtis’ work was published in 2000 containing a foreword by J.D. Horse Capture.

In Indian homes all across the country, photographs hang on the walls over fireplaces and dining tables, in living rooms and dens. These priceless images help modern Indian people maintain links with their past.”

As art and as an ethnography, Curtis’ images are filled with meanings. None say all that can be said. It’s for us to fill them with meaning. For us to take them forward, to interpret what we see in our own time and life and in our own photographs.

But boy, do these images inspire me!

Edward Curtis Portrait

Edward Curtis Field Techniques

Curtis developed his images in a tent while another tent served as a mobile portrait studio. You can imagine how the diffuse light through the canvas will have helped.

Curtis and Myers would often write the text for the books over the winter in a cabin.

Our camp equipment weighing from a thousand pounds to a ton, depending upon distance from a source of supplies; in photographic and other equipment there were several 61/2 X 81/2 cameras, a motion-picture machine, phonograph for recording songs, a typewriter, a trunk of reference books, correspondence in connection with the work, its publication and the lectures all from the field. Tents, bedding, our foods, saddles, cooking outfit, four to eight horses - such was the outfit. Someone has to boss the job; usually that falls to me. Everything must be kept on the move that no time is lost. Teams have to be bought, supplies secured, both commissary and photographic, arrangements made for getting and sending mail. On long stretches the whole outfit has to be shipped... and, withal, the one thing that must never be lost sight of, the purpose of the work; a picture and word history of the Indian and his life. But at times the handling of the material side of the work almost causes one to lose sight of art and literature. (Edward Curtis, 1907 Speech)

Edward Curtis - Working in the field

Edward Curtis - Photographic Process

Curtis used a number of techniques, some of which he amended to his own formula. He photographed glass plate cyanotypes, photo gravaure, and orotones, which he renamed cur-tones after developing his own methods.

Cyanotype Process

In the cyanotype process a glass plate is exposed in the camera, it is developed as a negative and then used to make a positive print.

The cyanotype process was introduced in 1842 and used a solution Amomonium Iron3 citrate that made a blue-tinted print on paper.

The process became popular because it was simple for the time. Although Curtis made many cyanotype prints in the field, very few survive due to their environmental fragility.

Edward Curtis - The Oath - Glass Plate Negative (Source: critical commons)

Edward Curtis - Wisham Female Cyanotype (source critical commons)

Orotone Process

Gold-toned photographs were very popular in the early 1900’s. They were printed on glass and known as Orotones.

Curtis customised the process and renamed it the Cur-tone process. He printed positives on glass, backed with a mixture of gold pigments and banana oil.

Edward Curtis 1904 - The Vanishing Race - Navaho Orotone

Photogravure Printing

Curtis specialised in photo-engraving. A negative image is printed onto a gelatinous surface and fixed to a copper plate. Chemical baths dissolve the gelatin leaving a postive etching on the plate. The copper plate is then used to make high quality prints for publishing.