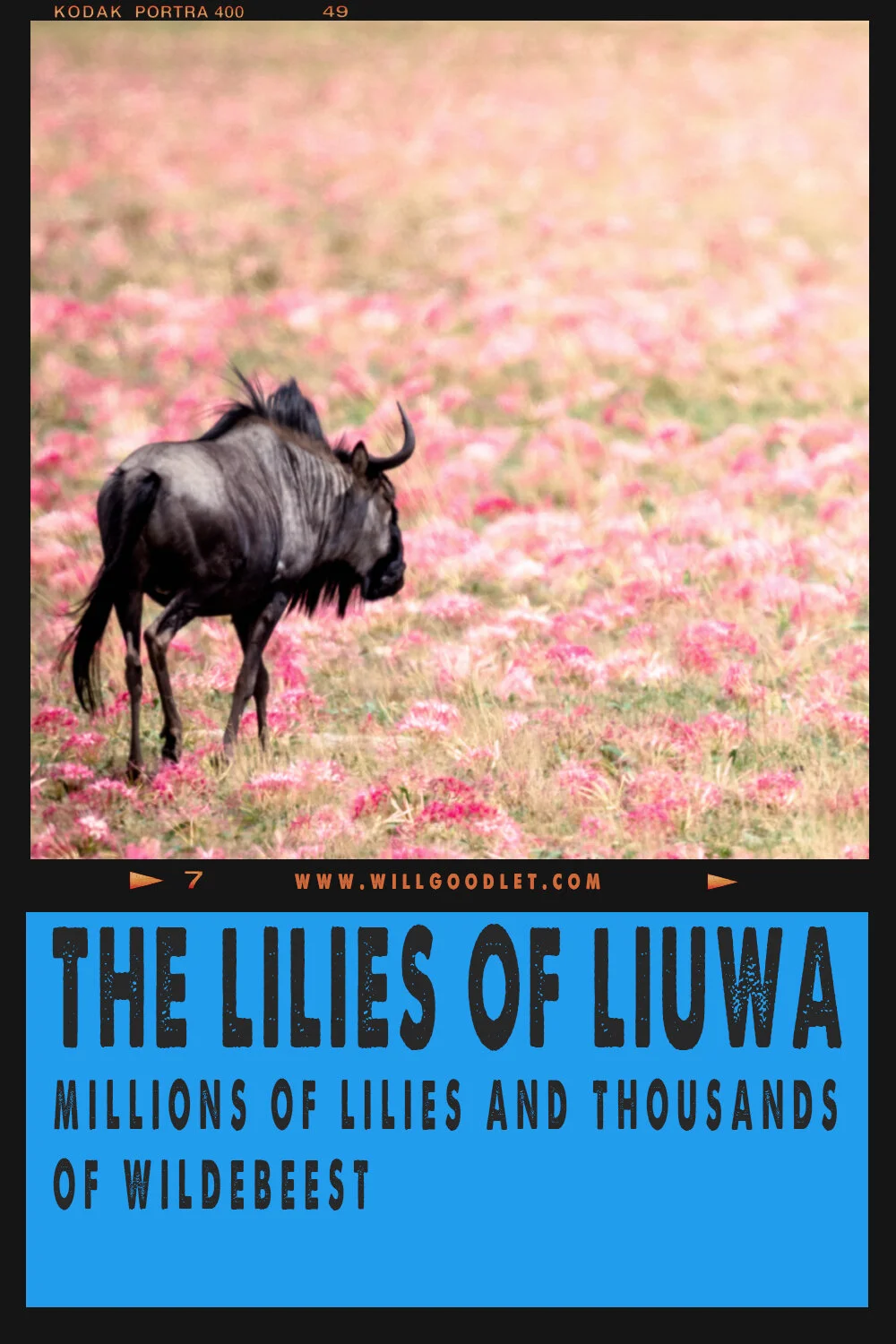

Adventures with Film: Strange Shadows

It’s a long time since I used film. Somewhere back in the 1990’s I lost contact with it and the 36 shots I took each holiday.

I used to just pick up any old roll of ISO100 or ISO400 and be about my business of happily snapping scenes - usually the backside of a Zebra as it ran into the bush - you know the kind of thing!

Recently I decided to give film another try, mainly because I desperately wanted to use Medium Format cameras and digital ones are far too expensive!

So I found a Mamiya 6x7 from the late nineties and started on my little adventure with 120 film.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro ii + 110mm F2.8 Lens - Kodak Portra 400

120 film is bigger than the box film that goes into 35mm cameras; those who are old enough will remember it. 6x7 is the format of one of the larger medium format cameras (6cm x 7cm) is the size of the negative, so roughly 5 times the size of a normal 35mm digital sensor.

There are 10 shots a roll in this format and each shot costs of about R16, with developing.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro ii + RB 55mm lens - Kodak Portra 400 (the orange edge is due to a possible light leak or poor processing).

So why do I want to photograph with medium format? Well that is easily answered!

The large ‘sensor’/negative allows for a much finer control of depth of field as well as the ability to situate your subject in a wider frame. It might not sound like much, but I swear if photographers were singers, they would all be singing about the medium and large format ‘look’..

There is a textural quality to film and it is a beautiful thing to see.

Mamiya RZ67 Proii + 110mm F2.8 Kodak Tri-x

Now, I would love to use medium format digital cameras but there is a catch with them besides the expense. They are larger format than 35mm but they are still far smaller than film medium format.

So what, besides the format, is the appeal of film?

Mamiya RZ67 Pro ii + 110mm F2.8 - Ilford Delta 100

Sadly, these days, it can be a struggle to achieve great clarity and detail. Much of the reason for this is because in the digital era we tend to scan film instead of using an enlarger and printing from it. The scanning degrades the quality a lot. One option is to print optically from the negative and then scan the enlarged photograph instead - especially with 35mm film which is more difficult to scan with consumer grade scanners.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro ii + 55mm Rb lens - Kodak Ektar 100 - again with some leaks or developing flaws

But it turns out film is an exceptional medium despite that. One of its special properties is the quite extraordinary things it does with highlights. There is no sudden point, as in digital, where they just drop out, it’s an even aesthetically pleasing shift in tones.

Once you recognise the differences it is easy to spot the digital flaws in photographs. Some of these are the darker ring we often see around digital shots of the sun, the pixel bloom around highlights or missing colours - especially reds.

Mamiya RZ67 Proii + 110mm F2.8 Kodak Ektar 100

When I started shooting film again, just about a year ago, I had read about the interesting things it does with highlights, so it wasn’t this that surprised me.

Instead, the surprise has been the way film works with shadows. Unlike digital, film doesn’t just blow out with overexposure. It’s a hard concept to grasp for one so immersed in digital photography.

Mamiya RZ67 Pro ii + 110mm F2.8 Kodak Ektar

Instead, film builds depth, the light-sensitive emulsion just gets more solid (darker as it is a negative).

You can overexpose a film 3 to 5 stops and it often looks pretty much the same! Especially when we don’t scan it and use ‘old tech’ enlargement instead (scanners lights are not powerful enough to ‘see’ into the built up emulsion so don’t do a very good job with over-exposed negatives).

Mamiya RZ67 Proii + 180mm F4 - Ilford Delta 100 developed at home by yours truly...(some people criticise the framing on this image, but do a google search for wildlife shot with a Mamiya 67 and see how many you find! The viewfinder waist-level & back-to-front and the focus is centre only. I was very pleased to make this shot!)

So, as the highlights build depth during an exposure, the shadows are brought up. It’s like you start to see into the shadows without the corresponding blown highlights. The histogram just keeps extending to the left and on the right side, the highlight side remains pegged.

It’s a disconcerting and beautiful thing, it really takes some getting used to and some time to understand, especially as a digital shooter.