Lilies of Liuwa

“If you have men who will only come if they know there is a good road, I don’t want them.

I want men who will come if there is no road at all.”

My mother was born in the far north of Zambia. My great-grandparents lived there in the in an old house with a shingle roof. It was built on the side of a beautiful wooded hill overlooking the mysterious and remote Lake Tanganyika.

Zambia is special to me, even though it took me 35 years to find my way there,

Standing alone in my grandfather's ruined house, shortly after my mother's death and not far from where the explorer, David Livingstone, ended his days, was one of the loneliest things I've ever done.

Lake Tanganyika the longest lake in the world and second deepest.

Kutula in the 1960’s

Kutula 2008.

The view towards Lake Tanganyika

Two thousand, five hundred kilometres from home, the trees drew close and the light grew dim as the rain marked time on that old tin roof. In the remnants of my mothers’ small bedroom, I thought about life and death and what it could all mean.

As I drove southward, the mist lay heavy over lake Tanganyika and it seemed to me as if the road back was impossibly long, with very few friends to be found along the way.

The long road South, 2008.

Ever since that day, I've been nervous of the sheer scale of Zambia. It feels too remote, too far from home and too foreign, with armed road blocks outside every major town and liquor stores, complete with rambunctious clientele in every village.

“It’s never long before the marching grey forests draw closer, the thick green silences sound louder and that repressed fear surfaces, For in Zambia, one can still be an explorer.”

Downtown…

Driving home, in a remote part of the country, I was lucky to escape a barricade of broken glass bottles designed to shred my tyres. As I nervously picked the glass out of the rubber, I waited for a club to strike the back of my head. It seems I got away because, at 3am, my would be hijackers had gone to bed!

The old Abercorn Arms - my grandad’s hotel

Now, whenever I cross the Zambezi, I feel as if I've entered the true heart of Africa. It's never long before the marching grey forests draw closer, the thick green silences sound louder and that repressed fear surfaces, For in Zambia, one can still be an explorer.

On this trip my friend Grant Fairley and I were to explore the rarely visited and remote lands west of the Zambezi.

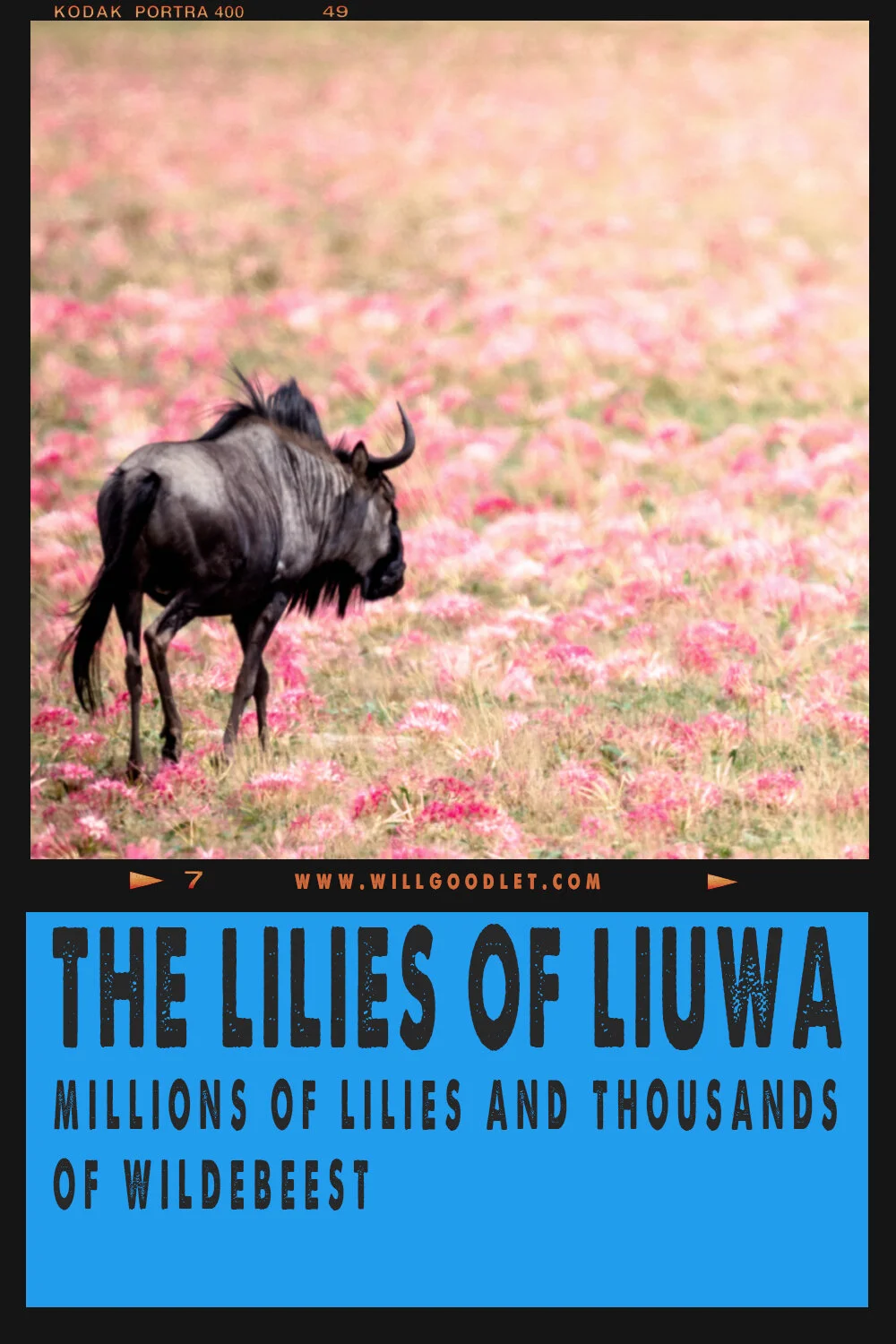

Sandwiched between the floodplains of Barotseland and the Angolan border, Liuwa plains is a vast area of sandy soil and grassland girded by the Zambezi and the Luanginga rivers.

Red-necked falcon chases a barn owl

It's famous for the 45,000 wildebeest that follow the thunderclouds from one side to the other; it is Africa's second largest migration. It's famous too, for its clans of daylight-hunting hyena and even more so for the Lady of Liuwa; the last surviving lioness of the plains.

However, the spectacle that drew me back into Zambia was none of these things because Liuwa is also famous for its lilies. When the rains come they flower and stretch, like vast velvet carpets - millions of them.

Wildebeest in a field of lilies

More Bedtime Reading?

An occasional newsletter with cool tips, resources and info from the world of nature photography…

Facilities are minimal, a basic campsite, no fence, and a hand-pumped cold shower with some firewood are all that you should expect or need.

The beauty of basic is that there are few other visitors to this wilderness. It is quite possible to drive for hours, even days, without sighting a soul and when one does, it’s almost obligatory to stop and swap stories.

Liuwa is crisscrossed by sand tracks. They all look identical, and it is very easy to become lost in the featureless expanse, even with a GPS. If in doubt, all roads lead to Rome, as they say, but in this case, Rome is the village of Kalabo situated across the pontoon bridge over the Luanginga river.

Male and female Oribi watch warily

Wildebeest amongst lilies

For wildlife photographers, Liuwa offers a very special privilege; we are allowed to exit the vehicle as long as we stay within 10 metres of it. You see, the 50 strong packs of Hyena are organised, not like their southern cousins, so be careful if you decide to flout the rules and wander – there will be no one to find you!

Being on foot means we can change perspective, either by climbing onto the roof or lying prone on the ground. Each one offers something quite special and different.

Expect to bump into villagers or fishermen on the plains. The wild animals share their space with humans and for the most part, they seem to get along. We spent some time with fishermen at a seasonal pond, photographing them laying their nets; the catfish stood little chance of escape.

Almost too big for the frame, a hyena walks by, a metre from where I am squatting and waiting.

Ox wagon on the way to Kalabo

A Fisherman and seasonal pool

The plains are special in this respect too, for it is rare, these days to find people living on the edge of wilderness. It's a foreign concept when it shouldn't be; in the past we all lived with nature in this way!

This lonely place, set in the heart of Africa remains wild in a way that more established parks like Kruger can never be. It's still a place where one must employ ones' wits. Have a care for one's person and life.

Nature still writes the rules in Liuwa, for a little while at least and this is all the more reason to seek it out - before the new roads and bridges bring ‘progress’ to this jewel in the west.

A lily of Liuwa

How to get to Liuwa by road

Getting to Liuwa plains used to be a little touch-and-go. The problem has always been the Zambezi and the Zambezi flood plain. You see, there was no bridge over the river and when in spate you can get stuck on the eastern, or worse, the western bank with no way back until the end of the rainy season!

So my trip to Liuwa was tense to say the least. I needed the spring rains to fall in order to witness the lilies but I was also risking being trapped on the west bank of the Zambezi.

An immature Bateleur takes flight.

Crossing the Luanginga at Kalabo

These problems have been alleviated to some degree by the building of a massive bridge and causeway over the floodplains between the western capital, Mongu and the village of Kalabo. This means, that even in the rainy season when the Zambezi floods, it is possible to cross.

A second bridge, further south, near Sioma has also been finished, which means the pontoon crossing (for which one can wait 2 hours) is no longer necessary.

All this development means that it is now possible to drive from the border at Katima Mulilo straight through to Kalabo without needing to use either of the two pontoons.

Grey crowned crane in the morning

Zebra wary of hunting hyena close by

The treacherous crossing of the Zambezi flood plains is now via raised and tarred causeway. However, there is one final hurdle - the pontoon over the Luanginga at Kalabo. It is quite possible that if the river rises quickly, that you could be stuck on the northern bank - in Liuwa, with no way to get out. Worse still, the plains themselves sometimes flood and to stay dry you would need to find an island.

For this reason, the rainy season is dangerous and you should plan carefully and keep one eye firmly on the weather.

If you approach via Kafue from the east, the road is also good (although there was a long gravel section when I was there three years ago). The route would be Lusaka, Kafue NP and Mongu.

Road Tolls

Be aware that there may be council road tolls to pay in local currency. These gates can be very informal, consisting of a stick across the road and a rusty sign. There was one such toll of ZMK 65 near Sioma when I travelled. The pontoon crossing at Kalabo also requires cash.

Sunset over the plains

Local Currency

When I visited the entire banking system was down. I found the most efficient way to acquire local currency was from the touts at the border. Research the rate of exchange beforehand to avoid being cheated. You may find a better rate from a local shop stall trader just outside the gates.

When crossing the border, you are required to pay various levies in Kwacha & USD so make sure you carry each currency in small notes (no change available).

Looking for a sign